Read the first blog in the series, The rise and stall of patient safety: Why 22 Years of Industry Effort Has Flatlined, here.

In May 2018, to “encourage greater coordination of collective patient safety efforts,” the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) convened a voluntary steering committee composed of more than 20 leaders representing health care systems, federal agencies, professional societies, accrediting bodies, and other patient safety advocates. Just over two years later, in September 2020, the committee released a 41-page report, Safer Together: A National Action Plan to Advance Patient Safety, which found that “despite substantial effort over the past 20 years, preventable harm in health care remains a major concern in the United States.”

Jay Kumar interviewed many of the report’s contributors for the Patient Safety & Quality Healthcare (PSQH) article, IHI Rolls Out New National Action Plan for Patient Safety. A common theme emerging from those interviews was the need to do more. While the collective effort applied is unquestioned, the results have yet to reach levels originally hoped for. “Patient safety, for all its years of trying, hasn’t progressed the way it should have,” said Helenn Haskell, the founder of Mothers Against Medical Error.

Other industries have greater success with implementing Zero Harm

Many of the initiatives in patient safety are modeled from practices — in particular, the adoption of technologies — that have been successfully introduced in other industries. The BMJ Quality and Safety Journal observes in Technology as applied to patient safety: an overview:

“Many industries have made significant advances in safety through the adoption of technology. Manufacturing has engaged in the reduction of human personnel through deployment of machine-based systems to produce high-quality goods. In aviation, there has been explicit acknowledgment of the potential for human error and a conscious effort to reduce error through the considered use of technology and automation.”

Yet progress in patient safety has not reached the same level of harm reduction that similar techniques have shown in other industries. What makes patient safety different?

A key difference: the human factor

It is tempting to treat all high-risk industries as similar and assume what works in one arena can be easily applied to another. The BMJ authors warn against this line of thinking:

“...healthcare is a much more ‘hands on’ activity than many other high-risk industries. Healthcare requires skilled interventions, adaptation, flexibility, and, most importantly, caring and empathy. Technology can support, but cannot replace human beings.”

Healthcare is different from other industries because the patient environment is far more complex than even the most advanced mechanical systems. The need to minimize negative impacts on the person being treated complicates decision-making even further. While procedures to identify and recover from anomalies encountered with an aircraft, for example, may be standardized, those related to the human body require far more nuance and contextualization. The addition of questions of ethics, compassion, and empathy makes standardization even more of a challenge.

Read Next: How to Choose the Best Healthcare Solution for Your Organization

Silos as a compounding factor

Another reason Zero-Harm efforts struggle in a patient safety environment can be attributed to the highly-siloed nature of healthcare organizations. Eileen T. O’Grady, Ph.D., R.N., N.P., in her book Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses, observes that this siloing often begins at the training stage:

“In no uncertain terms, the IOM declares that most care delivered today is done by teams of people, yet training often remains focused on individual responsibilities, leaving practitioners inadequately prepared to enter complex settings. The silos created through training and organization of care impede safety improvements.”

The PSQH article mentioned above cites Jeffrey Brady, MD, MPH, co-chair of the National Steering Committee and director of the Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety, who makes the creation of an “anti-silo effect” a key goal of the National Action Plan. “We know that no single person or organization alone can guarantee patient safety. Working together is a must,” said Brady.

Culture can also inhibit progress

A Journal of Patient Safety and Risk Management paper titled “What is the role of technology in improving patient safety? A French, German and UK healthcare professional perspective” explores, among other topics, linkages between technology and organizational culture:

Institutional culture can restrict the use and optimisation of current technologies

No innovation or improvement to technology will be successful if its use is not accepted or embraced by healthcare services and workers. A culture change at all levels of healthcare infrastructure, from clinician to international organisation, is possibly the greatest change that can occur to improve the benefits offered by current or future technology.

A recent study published in the journal Leadership in Health Services noted significant differences between how managers and staff perceived critical areas of patient safety (“PS”) and patient safety culture (“PSC”):

The worst results were in composites that are related to managers’ expectations and actions to promote and support PS. The staff felt that the organization is neither learning from the reported mistakes nor providing enough feedback. This approach does not support experiential learning, and the lack of feedback may cause staff to think that managers have little to no interest about reporting incidents (Auer et al., 2014; Mattson et al., 2015). Second, the lack of feedback and communication about incident reports may indicate that staff do not know the process involved after [a] report has been made. As has been suggested in the literature, a manager’s lack of attention regarding their perception by staff may decrease the number of reports and hurt the organization’s PSC.

Technology as a “silver bullet”

Technology is often pitched as the solution to all of these challenges. One study of the effectiveness of technology in healthcare settings reached the same conclusion:

“We conclude that health information technology improves patient’s safety by reducing medication errors, reducing adverse drug reactions, and improving compliance to practice guidelines. There should be no doubt that health information technology is an important tool for improving healthcare quality and safety.”

The promise of technology is, however, often undercut by frustrations end-users face when trying to make their process “work” within a new system. One vendor, in an article for The Hospitalist, summarized: “Workarounds happen all the time in healthcare because many of the tools and technologies impede rather than enhance a clinician’s efficiency.” Cheng-Kai Kao, MD, medical director of informatics at the University of Chicago Medicine, added, “We are talking about usability. We are talking about optimizing the IT system that blends into people’s daily workflow so they don’t feel disrupted and have to develop a workaround.”

Read Next: 6 Ways to Move Beyond the Patient Safety Status Quo

Technology can deliver large wins in the pursuit of improving patient safety. Yet it’s also the case that, when improperly aligned, technology can cause practitioners to be less efficient. An effective healthcare IT strategy will require balancing these diverging challenges.

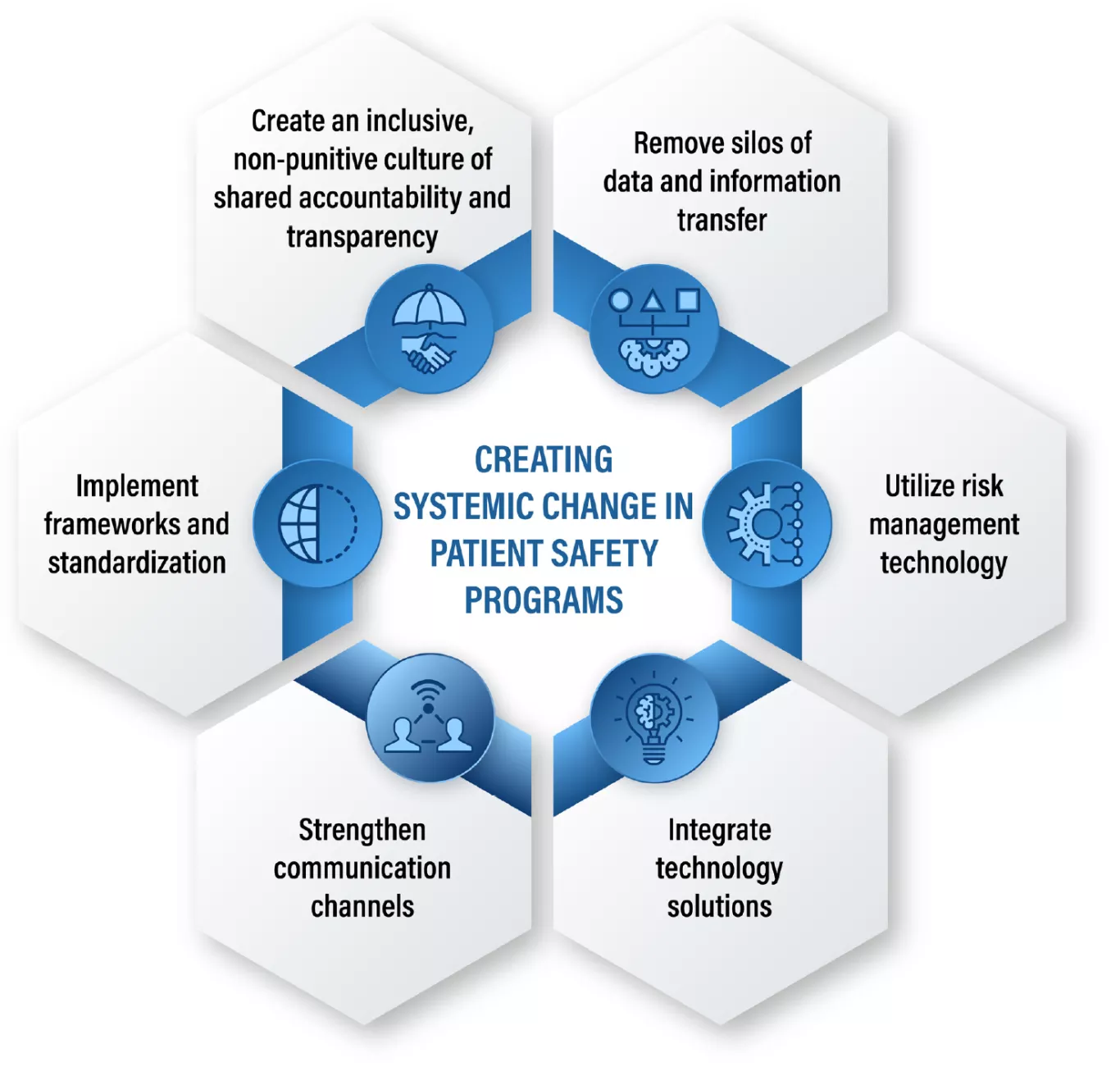

A framework of six coordinated imperatives

In a recent white paper, Improving Patient Safety: 6 Ways to Move Beyond the Status Quo, we propose an integrated approach that addresses the challenges of silos and patient safety culture roadblocks while still maintaining a patient-centric focus.

To address challenges to patient safety and quality, patient safety teams and leaders of healthcare organizations need to:

-

Create an inclusive, non-punitive culture of shared accountability and transparency, in which people at all levels of the organization are empowered to participate in event reporting. This starts with leadership, as change is cascaded throughout the organization, from the CEO, the board, and Chief Medical Officer to all employees.

-

Remove silos of data and information transfer that compromise operations, damage morale, and reduce the ability to maintain a productive culture.

-

Implement frameworks and standardization that leverage both qualitative and quantitative data, and democratize technology use throughout the organization.

-

Utilize risk management technology that works in tandem with existing systems and adjusts to the dynamic realities of specific locations and markets. Risk and patient safety solutions should make it easy and simple for everyone to submit anonymous incident reports with no fear of reprisal.

-

Strengthen communication channels to enhance alignment and decision-making capability, and foster the sense that everyone in the organization has an active role.

-

Integrate technology solutions so that the whole is greater than the parts. Solutions should be integrated to support ease of use and enhance end-user experience.

Compared to current fragmented approaches, the difference in this coordinated six-point approach is that it recognizes each solution, alone, does not deliver sustainable and organization-wide change. In this sense, for instance, remaining data silos prevent technology from enabling safety culture, which in turn limits the open communication necessary to close the loop on safety events and create transparency. For example, by automating and systematizing tasks such as adverse event intake, data-sharing and follow-up, clinicians and healthcare staff can focus on enhancing patient care and experience. In turn, this leads to a sense of empowerment and reduces the risk of burnout. These less-burdened healthcare professionals will ultimately deliver enhanced patient care, resulting in improved financial performance, retention, and reduced risk of further patient safety events.

An essential component: Configurability

As the Journal of Patient Safety and Risk Management article cited earlier points out, “Purchased technology solutions must be flexible enough to be customised to suit the structure and requirements of an institution.” Best-in-class technology solutions can be adapted to meet specific use cases rather than forcing users to reengineer processes to fit a technology solution. And as Dr. Kao explains in the Potential Dangers of Using Technology in Healthcare, “When the right things are made easier to do, people tend to do the right thing. And that is our goal.”

In a healthcare risk management system like Origami Risk, platform configurability refers to the ease with which client-specific requests can be accommodated without the need for time-consuming and expensive changes to code. This flexibility allows system administrators — either designated team members or an Origami Risk service team member — to quickly make system adjustments and deliver new functionality as required.

Examples of the configurability of the Origami Risk platform include the following:

- Fields and Codes – Screens, field names, and codes can all be tailored to fit the way departments, teams, or other stakeholders within (and outside of) an organization.

- User Settings and Permissions – Detailed security roles can be defined and applied to ensure users are only able to access the data and system components they are credentialed to access.

- Business Rules and Workflows –The ability to define the ways in which specific events are handled and to automate processes helps to reduce dependencies on manual processes that can be unnecessarily time-consuming and have the potential to introduce errors.

- Data Tools & Integrations – The ability to aggregate, cleanse, reformat, and report data to and from virtually any source helps to eliminate the silos of data that exist across many healthcare organizations.

To learn more about how your organization can make a lasting impact on its patient safety culture, start a conversation with us or download our latest healthcare white paper, Improving Patient Safety: 6 Ways to Move Beyond the Status Quo. In it, you'll learn about a six-point approach to patient safety and how the components are mutually beneficial.